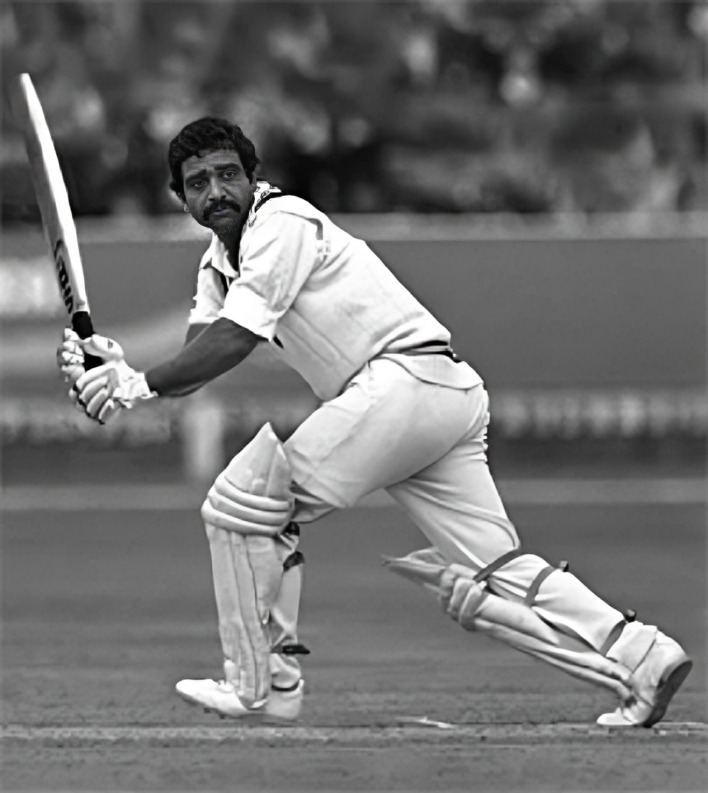

His name conjures up images of pure art, also science, of batting at its best — a canvas that Rembrandt van Rijn would have painted with relish. He integrated aesthetic judgment with truth and justice, no less: a theory of knowledge of what is merely artistic is also simply articulate. Not only that. He exemplified, in the process, his own spectrum of consciousness, a moment of truth — from elegance to refinement, from skill to exquisiteness — all without contradiction. In so doing, he elevated cricket, a sport like no other, into a genuine multihued alliance, or fusion.

It’s more than three decades since Gundappa Viswanath, or Vishy, ‘retired’ from the Test scene, and there hasn’t been a single player who has come close, forget about matching him in his god-gifted, truly refined, and sustained artistry. Vishy’s genius had in it all of nature’s bounty — like the insidious blossoming of a flower. His trademark, the square-cut, had an element of rare beauty: of a lotus in full bloom. Yet, Vishy never tried to command nature. He obeyed nature, all right. Nor did he ever endanger the fundamental character of the game: uncertainty and unpredictability.

Vishy was not merely a compulsive artist with the brush. He personified the painter in him, whatever the type of lithograph: in his case, varied, batsman-friendly, or hostile, wickets and laser-beam pace bowling, or wily spin. In so doing, he turned the old single-chord tool into a myriad instrument.

Vishy, who turned 75, last month [born, February 12, 1949], had all the requisites of a top-class batsman. He batted with a velvety feel: from a wrist as powerful as steel that ‘snapped’ at every scoring opportunity. In so doing, he gave a new dimension to cricket shots with his own sense of sublime delicacy, economy of movement, and action. A born stylist, Vishy’s game was beyond simulation: a derring-do dream, or hypnotic entity, far beyond the realms of imitation, or emulation.

Vishy had, early on, flattered only to deceive in his expression of an art that was all his own. His brilliant century on Test debut, against Bill Lawry’s Aussie ‘squad,’ in 1969 — after he had got out for a ‘duck’ in the first innings — followed by a few good knocks, now and then, were the only highlights, at one stage. Nothing else.

Came the calypso stars, circa 1973-74, under Clive Lloyd, and Vishy, the first Indian to have broken the ‘hoodoo’ of Indian batsmen who could not score another Test century, following their maiden ton on debut, hit it off wonderfully well. He was a transformed, energised batsman.

With his incomparable 139 at Kolkata [then Calcutta], and that super-duper 97 not out, at Chennai [then Madras], which he once told this writer, as being his best ever, Vishy emerged a great batsman. He had fulfilled his early promise. He did not look back until the 1982-83 series, in Pakistan, where he lost his magic touch — all of a sudden. Or, was he a ‘victim’ of the dreaded index finger? Go figure. A solitary series ‘descent,’ and the Little Marvel was banished from Test cricket. So much for our cricketing candour, vision, values and courage.

Vishy made 14 Test hundreds for India, most of them under testing circumstances. What’s more, India never lost a Test when Vishy scored a hundred.

A selfless batsman, who always played for his team, not himself, Vishy often came to bat with one motto in his mind, whatever the level of cricket: entertainment. This wasn’t all. He would also get out in the process, his own benchmark, by playing shots, which would otherwise have sent the crowd to the seventh heaven of the game.

While Vishy was disposed to taking risks, outside the off-stump, he was a majestic run-getter, in either form of the game, with an easy method. He treated the ball like a child; never gave it the pulverised treatment. His timing and placement were truly astounding. For one who was once rejected, by Indian

schools’ cricket selectors, on the basis of his short stature, Vishy was, indeed, India’s finest batsman after Vijay Hazare. His batsmanship, tall in its fulsome stature, represented a noble tradition, first fostered by Ranji and Duleep, and worshipped and practised by the likes of Dilip Vengsarkar, Mohammed Azharuddin and others, and then carried on by the likes of Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, ‘Very Very Special’ Laxman, Virender Sehwag, Virat Kohli, the super-duper ‘New-Age’ batsman, among others. Vishy was also fond of the drive, the pull, and the hook, aside from his feather-touch cuts. He executed them with prodigious grace and style.

More than anything else, Vishy played cricket the only way it should be played: as a sport, in the highest traditions of healthy spirit and competition. When he recalled Bob Taylor, who was given out ‘erroneously’ by the umpire, in the India-England Jubilee Test [1979-80], at Mumbai [then Bombay], in what is now a part of cricket folklore, Vishy had lifted the game to Olympian levels Baron Pierre de Coubertin would have been proud of.

Warm, kind, and generous, Vishy now carries with him, as he always did, an amicable frame of mind — a soft-spoken, liberal sense of character. It’s also one primal reason why he did not make a winning captain, despite being a good thinker of the game. Vishy, today, is unchanged. Times sure are a-changin’; but Vishy won’t. Because, he believes strongly in the true spirit of the game: nobility of purpose, not the end result. Yet, beneath his soft exterior, Vishy never ever gave up easily when it came to a test of skills in crises. He excelled in them. While others only talked, Vishy allowed his bat to speak for him. He still does that — as a cricket aficionado. He listens, but keeps his own counsel. Quietly. Effectively.

It’s high time every cricketer — big, or small — inculcated Vishy’s values and sense of being good even during a frantic ‘tussle’ between the bat and ball, and vice versa. That’s his stamp. It’s something that has truly made him the original composition.

More importantly, Vishy has always been adroit and adept at fostering harmony — the spirit and essence of sport. His philosophy of cricket has been impeccable and admirably earnest. It is a tenet that is, in the present dispensation, easier said than done. A difficult proposition, just as well, because not everyone can be like Vishy, or Sir Frank Worrell — the true victor of sport in one’s many-splendoured winning ways. If this ain’t inspirationally motivating to aspiring cricketers, what is?

There never was one like Vishy before, and there won’t be another like him — again.

— This piece was first published in The Hindu